I always have a good look at the prelims and end papers in books in the collection, and in this book published by Herbert Jenkins they are particularly interesting.

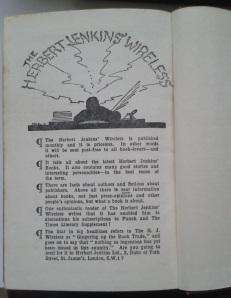

In the front there is a page titled ‘What this story is about’; a more unusual feature than you might think. Most novels of this period don’t have this kind of information or if they do it is on the dust jacket, which is often missing. At the end of the book there’s six pages of other novels published by Herbert Jenkins, and then on the last page there is an advertisement for ‘The Herbert Jenkins Wireless’.

Riley’s publishers Herbert Jenkins clearly believed in telling his readers the facts – or telling them they were getting the facts, which is not quite the same thing! I particularly like idea that a reader can now give up their subscription to Punch and the Times Literary Supplement. Jenkins was well ahead of his times in they way he marketed his books; I wonder if any other publishers of the period did something similar?

Back to Jack and John. According to Herbert Jenkins:

‘An understanding of the frailty of human nature, a timely word of advice, an expression of confidence and a generous gesture have often combined to lead a youthful offender from the paths of wrong-doing.

Of this fact Mr. Wyatt, the Stipendary Magistrate, was well aware when Jack Glover was brought into his court on a serious charge. Looking at the pale face of the prisoner in the dock, he believed that here was a case in which a fatherly chat would prove more effective than a prison sentence. He decided to put it to the test.

This story tells of the lasting effect on the lad of the magistrate’s words, of Jack’s mission to Wemby Moor, of his adventures on the way and of his reception in the little moorland town. It is a fine, moving tale in the true Riley tradition, as refreshing and as wholesome as the windswept moors themselves.’

So, the true Riley tradition! Yes, it is wholesome, and yes, Christian values are central. It is also a nicely told story.

Jack leaves his Yorkshire industrial town for the rural village of Wemby Moor, (apparently to be in the Lakes district) where he hopes to find traces of his deceased parents. He meets John, a skilled herbalist and unsuccessful businessman, frequently described as ‘foolish’ but also a good and religious man: “a better-hearted lad never wore out shore-leather and rammed Shakespeare into you’ (100). John takes Jack up on to the hills:

“Look on it, my lad! the winter is past, the rain is over and gone, the flowers appears on the earth, and the time of the singing of birds is come! Beautiful! and it is all mine and all yours. Over yonder is the sea – it is ours: this ringlet of mighty hills – ours; these trees, these dales, apparelled in their spring attire – ours. The whole of this magnificence – ours, because we have eyes to see it and souls to appreciate it and minds to appropriate it. … A God-given inheritance. Come up here to say your prayers, Jack, and to sing your Te Deum, as I do.’ (105)

Riley’s descriptions of landscape are vivid and full of feeling; those in the reading group who didn’t enjoy their Riley novel all mentioned how good the landscape descriptions were. For Riley, as this passage shows, appreciation of the landscape is part of the worship of God, for this is all God’s creation.

Jack becomes a successful businessman, but the accumulation of money is quickly shown to be only a small part of ‘making good’. Jack must also educate himself, and by the middle of the book he has a degree.

The surrounding cast in the village of Wemby Moor are all typical Yorkshire folk, ‘speaking as they find’ but underneath this Riley always puts of twinkle of humor in their eyes, or a hidden soft spot.

Rather fun characters are Barbara Hamerton, from the local ‘big house’, and her fiancé Larry. Larry is clearly a bounder, in a very modern 1930s manner. He drives his Lagonda too fast, hoots his horn and wears ‘a curiously patterned pull-over’ (131). This causes Jack to muse that there is something about the fellow he does not like… perhaps fair-isle sweaters, brought into fashion by the Prince of Wales in the 1920s, show a chap up as a bounder? The final confirmation that Larry is a bad lot is when he tries to leave their left-over sandwiches in a rock crevice when walking on the hills. Shocking.

Towards the end the plot become rather silly, with hidden documents and concealed identities suddenly revealed, and then at the very end there are happy marriages all round.

I can see how if you like what Riley does, this novel could be very appealing. It is ‘feel-good’ in an old-fashioned, improving manner. Nowadays, however, I suspect most of us do not wish to be ‘improved’!