In my final year at college we were offered the chance to take typing lessons in our free periods so, wisely as it turned out, I grabbed the chance.

While I never managed to achieve the speedy and accurate touch-typing skills The Spouse acquired, that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing because I took the inspired advice my father gave me when I was about 15 – “Don’t end up in a job where you type someone else’s letters.”

Instead I ended up as a cadet reporter on the business pages of Wellington’s Evening Post newspaper where my six-digit keyboard skills were more than adequate. At that time there were only two other women in the general newsroom and they were both in their 50s and had managed to get into journalism during the war years.

There was a Women’s News section, but it had its own little office tucked away in a quiet corner, ruled by a forbidding maiden lady with red hair who would grace the social circuit in autumnal chiffon.

She once bawled me out in the staff cafeteria for wearing a “cocktail dress” to work. It was a humble little floral brushed cotton number in dark blues and greens that I’d made myself. Long sleeves. Modest neckline. I think she took it for expensive velvet.

I asked my male colleagues why there weren’t more women reporters. One of the older men said it was because the chief reporter didn’t want them hanging round the tea urn gossiping all day.

The tea urn. Now that’s another piece of nostalgia. Every morning around 9.30 a tall, skinny reporter in his 50s – known as Long Tack – would head to the staff cafeteria and bring back the tea urn and a couple of pints of milk. The urn was placed on an upended square metal box sitting in a newspaper-lined trough designed to catch the drips.

For the next hour or so chaps would pour a mug of the ever-darkening tea and those not in the middle of an assignment would loiter round the urn, dare I say, “gossiping”. I never noticed the chief reporter fretting about them.

Anyone wanting coffee would have to go to one of the nearby coffee bars. The young court reporters had one watering hole on their route to Magistrate’s Court. The roundsmen, who were older, had another meeting place.

Compared with the newsrooms of today, ours was a very primitive place. There was marbled brown and cream lino on the floor, wooden desks with one deep drawer, one shallow drawer and a little recess all on one side. Overhead was a textured ceiling of soft substance. I know it was soft because we used to make darts and fire them at the ceiling where they’d stick into what I suspect might have been asbestos.

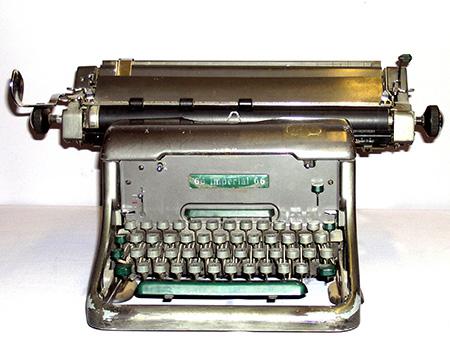

Having got a desk, I had to lay claim to my own office accoutrements. There wasn’t a chair and typewriter for each desk. The trick was to locate one of each and “personalise” it. Possession was one thing. Retaining possession was another, specially for a new chum. Once I’d sorted out an Imperial 66 and personalised it, I learned a good ploy was to leave a half-written story in the typewriter. That made it look like I was just out of the room briefly.

In spite of tea urn loitering and coffee breaks at the Coconut Grove next door, we did get out and chase stories and we developed our own little work rituals. After an assignment, mine was to spend a contemplative minute or two in a quiet cubicle in the terrazzo-floored facility next to the reporters’ room. There I would nut out the intro to my story. My ritual rarely let me down. The right words would come and my fingers would itch to type.

I’d head to my desk, get out my notebook, light up a Rembrandt cigarette and feed some copy paper into the machine. We had to take two or sometimes three “blacks” or carbon copies of our stories. One for the subeditors, one for ourselves, one for Press Association. Everything had to be double-spaced to allow room for editing.

The typing didn’t have to be secretarial-perfect. That’s what the x key was for. You x-ed over misspellings and grammatical errors. But you were respected if you could turn in good clean copy.

There was a certain adrenaline rush as deadline approached and from all around came the staccato tap of fingers on keys and the “ping” of the typewriter bell near the end of a line – a signal to hit the carriage return lever.

As you flipped the page out and wound in another “side” of copy paper, it might be time to light the next cigarette. At the end of the story, you’d fold the copy in half, place it in a cartridge and send it rattling down the Lamson pneumatic tube to the sub editors’ desk.

The advent of computers and the switch to cold type changed everything. The typewriters were silenced forever. People were no longer allowed to smoke in the workplace. Offices became quieter, cleaner.

I love my computer and it can do some very clever things. But listening to it clack along like a typewriter as I write this piece has given me a lovely warm feeling of nostalgia. Sorry, Steve Jobs, subtle little keyboard thuds don’t do that.