My husband, who is a certified wise guy, posted on his Facebook page this morning: “Ask not what poetry can do for you, ask what you can do for poetry.” Now, I get it. It’s a week for inaugural wisecracking and Monday morning quarterbacking, and some thoughtful reflection on the role of poetry in inaugurations and in public life generally. Like here and here.

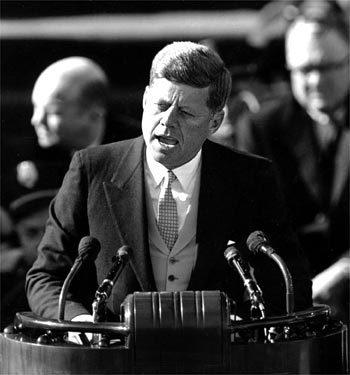

But as much as I love, admire, and respect that wise guy, his reversal of President Kennedy’s famous challenge, has been bugging me all morning, and I spent my walk into work wondering why. I actually think that his smarty pants reversal is the problem. That’s what we do all the time. We ask what we can do for poetry rather than letting poetry do for us, letting it work on us in some real way. We spend our time thinking about what poetry we are going write and how our brand of poetry is going to save the art from the wreckage that is modern life.

If David’s certification is from the College of American Wise Guys, my certification is this: I’m a Certified Work Horse. I like to ask what can I do?, and then I take joy in doing it. So, I get it. It’s an American truism – stopping being takers and start being makers. But, in this case, I think we could take a little more and pause for a little longer before we start making.

It’s a joke among poets—a sadly accurate one—that no one reads poetry except other poets. And we all suspect that even there, the reports of our reading are greatly exaggerated. But, I think many of us—myself included—all too often read for utilitarian purposes. We read poems to improve our own craft, we read poems to size up the competition, we read poems to keep up with the patter on the Rumpus and Facebook and whatever other poetry water coolers are available to us.

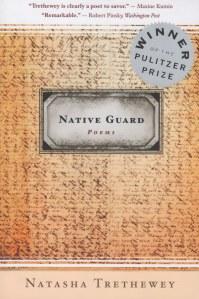

But too infrequently do we read poems and let them “do” for us, let them work on us. The most recent example I can think of is when Natasha Trethewey won the Pulitzer for Native Guard. After the award was announced, I ran right out to buy the book to see what all the fuss was about. Again, impure purposes—Who was winning prizes? How does this book work? And, I will admit that after I read it, I was let down and left wondering. The poems were so quiet, so reserved. I really couldn’t figure out what all the fuss was about. I was vaguely disappointed, but shrugged it off and went on.

But, here’s the thing. As I went about my life, I couldn’t stop thinking about those poems, about their poise, about their truthtelling, about their hauntedness. I couldn’t stop thinking about this:

The Daughters of the Confederacy

has placed a plaque here, at the fort’s entrance—

each Confederate soldier’s name raised hard

in bronze; no names carved for the Native Guards—

2nd Regiment, Union men, black phalanx.

What is monument to their legacy?

All the grave markers, all the crude headstones—

water-lost. Now fish dart among their bones,

and we listen for what the waves intone.

Only the fort remains, near forty feet high,

round, unfinished, half open to the sky,

the elements—wind, rain—God’s deliberate eye.

Even though I read the book for all the wrong reasons, it got inside me despite myself. It worked on me, it changed me. And though I still read for reasons that are careerist and utilitarian, I am a better person, a better citizen for having let Native Guard do for me.

We are a country of makers, that’s for sure. And that includes poets—we make. But, once in a while, I think it would behoove us to linger on the couch, to take a little more from poetry and to ask not what we can do for poetry, but what poetry can do for us.