Artwork by James Grover

The till is closed. The familiar sound it produces makes the shopkeeper smile affectionately. He is a contented man. He is proud of his shop. He is proud of his loving wife. He is proud of the three sons in his life. He is proud of the doctor, his eldest. He is proud of the chef, his middle son. He is even proud of his youngest, despite him being the black sheep of the family, a troubled young soul who has caused a lot of anxiety. He is proud of his niece and nephew who assist him in the shop. He is proud of his three young grandchildren who light up the days he spends with them. He is proud of his achievements in life.

His last customer has left wet footprints on his clean tiles. Muddied rainwater outlines the shape of the boy’s footwear. He smiles at their trail. He makes his way around the counter. The plastic bucket of lukewarm cloudy grey water and the worn out mop married to its side are fetched. Humming an old Indian folk song from his youth the shopkeeper cleans away the trail of footprints. Erasing them and the visual evidence of the boy having been in his shop.

When he is finished he returns the bucket and mop to their resting place, to be retrieved the next time a customer comes in and leaves their own trail behind. He attends to the shelves that already display perfectly aligned produce, but he like to keep busy. The folk song he hums has been passed on for many generations. Despite the uplifting melody it emanates, the contrasting lyrics harbour dark melancholy as they recount the tale of a boy in a village who befriends a wolf, but when the people of the village discover this they kill the wolf for fear of the boy, and their, safety.

There are not many things in life the shopkeeper dislikes, but those lyrics are one of the dislikes on his short list. It is the harmonious music of the song that puts a smile on his face because it takes him back to his childhood when his own grandfather hummed it to him. His grandfather also disliked the lyrics and did not want to instil a negative message into his impressionable young grandson. The shopkeeper’s grandparents and mother were the bedrock of his youth. His grandfather was looked up to as the father figure for his own passed away during his infancy from cholera. The shopkeeper, in turn, has kept the tradition by humming the soft and soothing sounds to his own children, and in recent years to his grandchildren.

He is brought back to the now with the aggressive entrance made by the inebriated feisty young woman who was causing a scene on her phone outside just moments before. Half stumbling through the door she yanks the strap of her small black handbag up her shoulder, dropping the mobile phone onto the tiles. She swears out loud as the little device scurries across the floor like an escaping mouse. The shopkeeper goes to his customer’s aid and captures the phone for her. In his hands he checks it for damage before handing it back with a warm smile. “It’s ok,” he tells her. She takes the phone with a sheepish look and mouths thank you.

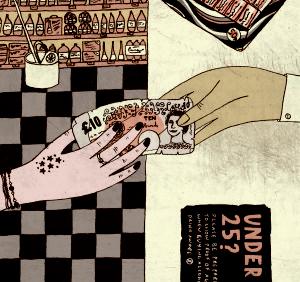

As he makes his way back behind the counter the woman asks for £10 worth of phone credit for her mobile tariff. “Certainly,” he replies and hands it to her. An old crumpled, yellowing note is given to him in turn. With the familiar sound of the closing till comes the familiar smile on his friendly face. The alcohol-induced glaze over the woman’s eyes is temporarily penetrated and she smiles soberly back at the man. “You have a very happy face.”

He gently places his hand on his chest where his heart is concealed, tilts his head to one side and nods humbly. “Thank you so much.” She turns on her heel and makes for the exit. “Be safe outside,” he warns her. The door closes and she waves from the other side of the glass. He waves back and once she has disappeared he goes to fetch the mop and bucket once more.

James Massoud