I hate to do this. But I am going to have to take issue with the great Joseph Campbell, from whom I have gained solace and comfort and inspiration from for nearly as long as I can remember. Campbell was one of the world’s foremost experts on myths and culture. And yes, he was a genius. And a cultural icon. But let me back up.

I am in a mess at the moment. I don’t ever remember saying—or even thinking—the dreaded words writer’s block. I have always had a backlog of ideas and a drive to wrestle human experience into poems or essays or even wisps in my notebook. Not so right now. I have no idea what I am doing or why I am doing it. Poems are turning to ash in my mouth. The essays I have started feel self-indulgent or derivative or—worse—wholly unnecessary.

It is both terrifying and bleak. So I am reading like a fiery fiend to try to find a path back into art-making of any form. My pen is poised over my notebook, but I will take anything. Karaoke. Macramé. Paint by numbers. Anything. This dead and doubt-filled mood feels like the mood that overcame me when I first heard someone describe dark matter in space—ice-cold, menacing, lethal to everything I thought I knew about humans’ role in the universe.

So enter Joseph Campbell. For many years I have turned to a little book entitled A Joseph Campbell Companion, a compendium of teachings by Campbell collected by the poet Diane Osbon, with most of the material coming from Osbon’s attendance at a month-long seminar with Campbell in 1983 at the Esalen Institute in Northern California. The book is generous and wide-ranging and is intended to inspire.

And boy do I need some inspiration, particularly when it comes to art-making. So, I skipped ahead to the section “Living in the Sacred,” which as I remembered it, is a paean to the transformative power of art. And sure enough, there is this lovely:

Art is the transforming experience.

The revelation of art is not ethics, not a judgment, nor even a revelation of humanity as one generally thinks of it. Rather, the revelation is a marveling recognition of the radiant Form of forms that shines through all things.

There. Of course, the invocation of the Form of forms doesn’t help me with my immediate problem—not being able to find a poem with both hands. But it does reassure me that art matters, that it is the light in our fumbling quest to become more human. More alive.

But then, a few pages later, is this:

One application of the artists’ craft is in doing something like making a turkey dinner, another is in creating art that is of no use whatsoever except esthetically. When I use the word “art,” it has to do with “divinely superfluous beauty” and esthetic arrest. There’s no esthetic arrest in eating a turkey. That’s life inaction, doing what it has to do, namely eating something that’s been killed, putting it into your system. It’s totally different from esthetic arrest and recognizing the radiance. Are you going to look at the object or eat it? Eating the object is related to desire and loathing.

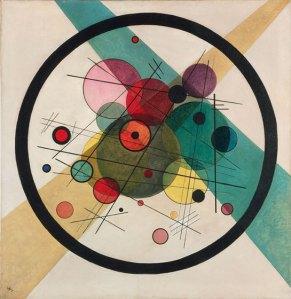

Vasily Kandinsky, Circle with a Circle

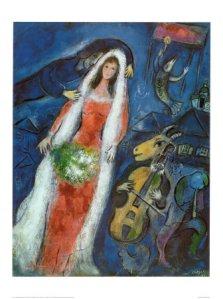

And there is where the issue of taking issue comes in. I am all for superfluous beauty. In fact, the transcendent geometric forms of Vasily Kandinsky are among the paintings that matter to me the most. I can almost see the shimmering sub-order of the constellations vibrating behind them. But the paintings of Marc Chagall are also among those I treasure most. Chagall’s paintings are magical and otherworldly as well, but they also celebrate and embrace the world of cows and churches and broad-hipped weddings.

Marc Chagall, La Mariee

For me, there is even more to it than that than the difference between Chagall and Kandinsky . While I am in the dark night of the soul with regard to poems, I still have to cook dinner. It is high summer, so I am in my garden every day. And, I am still knitting baby blankets and prayer shawls. And it is in those every day makings that I can still find the “radiance” that Campbell talks about, even when the well of pure art-making is dry or at least very, very low.

Every day, I am immersed in the transformation that comes from heat and water and time. In the application of those elements to raw materials—peppers and tomatoes, radish seeds and soil, wool and cotton—I get a glimpse of the order of things. I get a chance to join in the steady business of creating and re-creating form. For me, that is not “life’s inaction” nor does it relate my peppers or pea shoots or yarn to “desire and loathing” because those transformations have practical, daily functions. As it turns out, the very fact that I can transform a pepper from our garden into chile rellanos or ratatouille makes the idea of making a poem again seem more possible. It makes it seem as if the order of the universe favors the makers after all. It makes me want to stay at my desk and ride out the doubt and flailing and suffering in hopes that there are still poems to be written.

And so I guess Joseph Campbell did work his magic over me once again. He did arrest and inspire and bring me back to what matters, not with solace exactly, but with provocation and a turkey dinner.