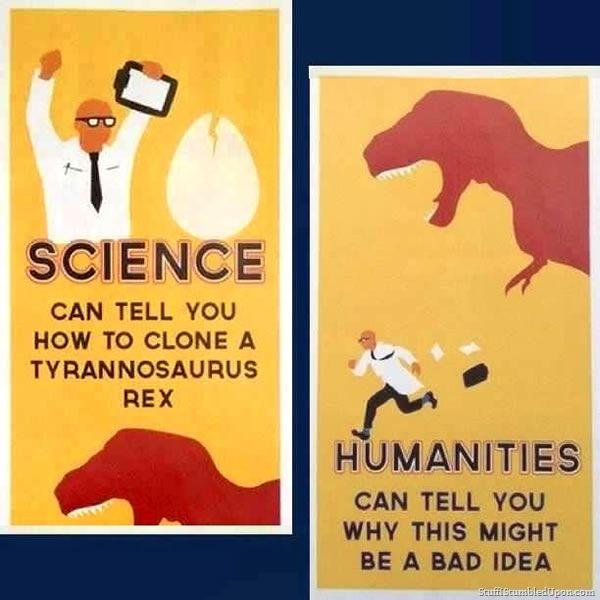

“Science can tell you how to clone a tyrannosaurus rex,” says a popular Internet meme. “Humanities can tell you why this might be a bad idea.”

The human race is learning how to clone, figuratively speaking, quite a few dangerous dinosaurs.

Scientific research has created new frontiers in food. Some processed snack foods taste so good, I won’t even stop eating them until the general anesthetic kicks in, right before my latest bypass surgery.

Wireless cameras and weapons systems have allowed military personnel to kill people with unmanned flying drones, which sound really cool until I think about our strikes in other countries and the "collateral” deaths that ought to be on the United States’ conscience.

Internet entrepreneurs and affordable video devices have enabled me to spend hours – when I might have been bogged down with something like grading papers – watching people do stupid stunts and injuring themselves. (A show called “Ridiculousness” on MTV is a half-hour devoted to viral video clips of people trying stupid things and getting hurt, like “Jackass” with a cast of regular people, a cast of thousands of normal folks.)

I’m not the first to notice that progress – specifically, technological and scientific progress – is an absolute social, cultural, and political value in America. I’ve even heard George Will, the Pulitzer Prize-winning conservative columnist and scold of government spending, say he believes space exploration is a good use of government money.

Who can argue with that? America is the birthplace of the aircraft and the telephone. Royalty and leaders from around the world come to America for the best medical treatment. Even one of our former vice presidents invented the Internet (sorry – that’s an old one, but I couldn’t resist).

Few people aside from the Unabomber’s sympathizers oppose scientific and technological advances. Even behind the pop-culture stereotypes of some groups, scientific and technological progress remains an assumed good.

Growing up in North Carolina, I knew a lot of Christian fundamentalists. They all worked for global computer companies. They were creationists, to be sure, but they knew their calculus, their programming languages, and their home computers. They had Bible studies in their nice suburban homes, which were outfitted with the latest refrigerators, microwave ovens, and television sets. Lovely lawns, too.

With progress as an absolute American value comes a belief: If we can do something, we ought to do it.

This might be due to the decreasing wisdom in our culture. Mass media brings us more information, but we have less knowledge and even less wisdom.

That was Neil Postman’s take. Postman, author of Building a Bridge to the Eighteenth Century, wrote that information was merely facts, while knowledge was the incorporation of information (facts) into useable forms. Finally, wisdom used one type of knowledge to evaluate another type of knowledge.

If you think about it, specialization makes the isolation of types of knowledge even worse. Advances in knowledge branch and branch in special new directions and sub-categories until some guy somewhere knows everything about the tailfin of a rare tropical fish -- but he cannot break into his new refrigerator.

Or, for example, when someone figures out how to clone a tyrannosaurus rex, as exciting and cool as that might be, he might not have any idea why it’s a bad idea to progress to actually doing it.

-Colin Foote Burch