She died on Thanksgiving Day, hours before dawn. We had known it would be soon, but had hoped someone would be with her when she went. As it was, we were spending twelve hours a day at her bedside, taking turns holding her hand and waiting. But she met death on her own terms, and really that seemed fitting, even if it haunted us.

I don’t like to remember her as she was in those last days, but I do, especially on Thanksgiving. Her previously plump cheeks had been hollowed by cancer, her downy soft silvery hair like a cloud above the gaunt temples. The worst were her large, china doll eyes. They used to be a merry blue, but the morphine made them cloudy, like marbles. Like a ghost. The first time I saw what the morphine had done, the tears spouted from my eyes and I blubbered. She was already gone, though still here.

She had planned to make it to my sister’s wedding in San Francisco. She had tried to eat more, but the pain and digestive ailments had already done their insidious damage, evil elves hammering away where no one could see. She had grown too weak to fly. In the end, she watched the wedding video from a hospital bed just as the doctor flipped on the morphine drip and her suffering softened around the edges.

Drip. Drip.

At the end, it came down to monitoring vital signs: slowing of the heart rate, the shutting down of the excretory system, the decreasing need for IV changes. We became acquainted with hospital food, and we learned how to watch for death.

Death watch.

After I received the call early that morning, I thought, good. Good. It’s over. These thoughts were for grandma as much as for my mom, the caregiver during this drawn-out battle. It had already been a full week. We didn’t know why she hung on as long as she did.

I couldn’t cry. All my tears had been spent at her bedside, when she drifted away on the morphine haze, fading like a forgotten daguerreotype. It was then I knew she would never come back.

As I dressed myself that day, I remember the powerful need to be with my family, to be with my sisters who had shared her love and my mom who had shared her laughter and my dad who had treated her like his own mother. I drove to my parents’ house, playing the loop over and over in my head: she’s gone. She’s gone.

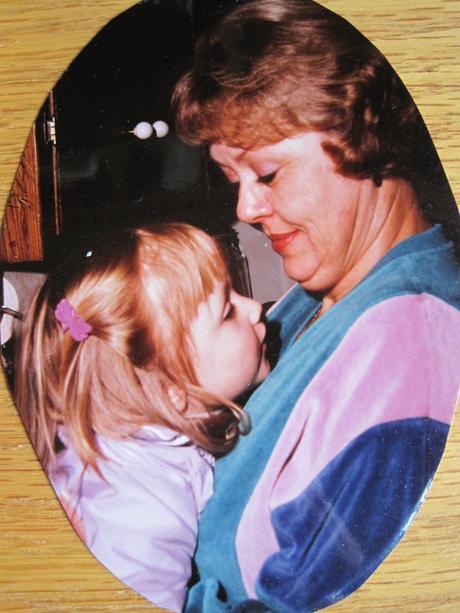

We made dinner together. We laughed over her need to control the density of the gravy and smiled faintly over her need to bake a pecan pie every year. She often came decorated in seasonal pins, in hand-decorated sweaters, in jewelry she made herself. She passed around hugs as if she had invented them.

That year, there was a hole over the stove as I stirred the gravy while my mom added more cornstarch. There was a hole as we sliced the pie and passed around cups of coffee. There has been a hole every year since, but we make sure we fill it with laughter when we’re together.

She’d have liked that.