Happiness used to be the clink of cheap wine glasses on a windy fire escape and the laughter of friends trailing into the night.

Then it was the way that a new pair of heels clicked on the pavement to the tempo of my masterfully adopted New Yorker gait.

Down the line, happiness became crown molding, fresh ranunculus's from the farmer's market on Sundays, and the sophisticated way my vintage-diamond-and-sapphire-ringed finger leafed through the New York Times.

For a good many years, it was one-handedly clicking the shutter of my camera in the early morning with a child kicking inside my belly, and one-handedly typing stories well into the evening at our round white formica table in our funny little Manhattan apartment with a baby nursing at my breast.

And later, without question, happiness became a blustery playground, a cup of coffee burning my lips, and again, the exhausted laughter of friends trailing into the wind.

I never thought that I knew it all. As a new mother, with a neatly stacked pile of folded swaddles and the teeniest tiniest pair of knitted booties sitting upon my dresser, people would ask me if it was hard. Was the sleep deprivation unbearable? Had my life completely transformed? The answer to all three, without question, was an unremarkable no. I felt somewhat guilty for this. Those early days were supposed to be burdensome and exhausting. They were not. I awoke in the morning with a content, if not stubborn, little girl, strapped her into her carrier, and headed out into the world. And life, for the most part, remained just as I had always known it to be: caffeinated, romantic, and, surprisingly, somewhat spontaneous. Dinner on the roof tonight? Yes, please. And outdoor concert at the park? Bring the baby! Weekend road trip? Why not?

As the first of nearly everyone I knew in the city to have a child, we were pioneers. And we knew nothing. So we walked into it with open arms and no expectations of any kind, cloth diapering and making our own baby food and living knee-deep in culture and music and excitement, and somehow, remarkably, it worked. I never read any books about parenting, and if I had, I'm sure I would have dismissed it all anyways. We knew instinctively everything we needed to: nourish the baby with the very best nourishment we could muster, cut her hair when it grew uneven (which took awhile, and has happened approximately a twice in her lifetime thus far), and love her.

I never knew it all.

By the time the second and third babies arrived, we'd moved apartments, left and returned to the East Village, said goodbye to many friends who'd abandoned the great Metropolis for greener pastures out west. When I walked down the street with my newest baby, still acclimating to the overflowing happiness of being a mother of three, passersby would not stop and giddily congratulate me as they had the first, and even second times around, but begin to smile at his tiny squishy face and then, as their gaze passed over the screaming two-year-old in the stroller and the straight-faced four-year-old walking with her hands on her hips, the corners of their mouths would shift and the smiles would morph into bewilderment, bordering on horror, and they would exclaim, "Ohhh, congratulations? You look like you've got your hands full!" My husband and I would joke about these all too common reactions. But looking back, what I really wished, is that one of them would have put a hand on my shoulder, and said, "It's ok. You got this."

I never knew it all, but the feeling of not knowing it all didn't set in until right around this time.

When a two-year-old Lucien, upon moving into our new 11th-floor apartment, dumped his entire basket of toy cars out the window, I felt my heart stop for half a second. There was an interim of about three days, an oversight on management's behalf, after we moved in, during which we were residing in the apartment, but the safety bars had not yet been put on any of the windows (as is required by law in NYC when there are children living in an apartment). They were a very nerve-wracking three days, especially since I was pregnant and had the attention span of a peanut, and Lou was two and had the climbing capabilities of a cat, yet little to no rational thinking skills. I remember being in the bathroom, hearing the thud of something hitting the top of the window air conditioner of the neighbors below, and lunging half-naked into the living room in horror. The mere moments it took to turn the corner into the next room were an eternity, and when I saw him standing in the windowsill, an unhinged window before him letting in a springtime breeze, his tiny hands holding an upturned blue wire car basket, tears began to well in my eyes. That was the first time I remember the thought crashing into my mind, "I can't do this."

When a newly five-year-old Biet gave herself two haircuts, in two days, I was furious. The first was just a little piece of hair from underneath, barely noticeable unless you were looking for it. The second, a perfectly centered, perfectly curled lock right in the middle of her forehead- chopped away. Right after I'd told her not to hold scissors near her face, right after I'd offered to cut her hair for her if she liked, she decided that an uneven one-inch chunk of fringe, front and center, seemed like a good idea. And of course, it makes complete sense. That's Biet. I should have understood from the get-go, from the time she was a tiny little thing in her knit booties, that of course she would cut her hair. But that was the first time I remember hearing the words of my father escape my lips: "How many times do I have to tell you?", "You do as I say!" and, most embarrassing,"That's enough, young lady!". After those first mutterings, it happened more and more. And perhaps my patience shrunk more and more. And as we all continued to grow, and life became more complicated, those frightening little words began to cross my mind more and more often as well, "I can't do this. I just can't do it all."

I don't remember the exact moment when I truly began to understand and appreciate the magnitude of my village, but I remember the people.

Perhaps I'm in the minority, of having to reach a breaking point before making real change. Or perhaps everyone reaches this point, and it's just that no one really talks about it. Or perhaps we all know nothing, and are just winging it day by day, year by year, and randomly finding one another along the way. But for me, it happened around the birth of Levon. Coincidentally or un-coincidentally, one of my best friends in the city happens to be on the same life-trajectory, as far as motherhood is concerned, as myself. We bonded when our eldest became best friends, our middle children are only months apart, and our youngest must believe, I assume, that they are brothers of some sort. That is how much time they spend together. To find another woman crazy enough, in this already chaotic city, to have three children within four years, is one of my greatest blessings as a mother.

One morning while trying to get everyone buttoned and brushed and packed for school, my brows furrowed in anger and frustration, my voice cracked in that awful way that a stern mother's does, and I yelled at my children, "Now we're late! Again! This is impossible!" I knew that it wasn't their fault- they were just being kids, with no concept of punctuality, no awareness of how wildly counterproductive it was to begin playing dress up now, when we were already fifteen minutes late trying to get out the door. But I yelled anyway, and as always, it did no good. The cleanest article of clothing I owned at the moment was covered in milk-stains, but at least it was black (I have a silly notion that one will always look at least somewhat glamorous in black, even in the most unfortunate situations). My hair was unbrushed, but looked very "downtown," I authoritatively convinced myself as we locked the door behind us. I silently hoped that I didn't run into anyone I knew along the way.

But of course I did run into a friend, just as soon as we stepped out the door. I ran into my friend and her three children. And her shirt had milk stains. And her hair was unkempt. And our eyes met one another in a way as if to say, "You too?!".

And that, my friends, was the beginning of the end... the beginning of the end of feeling burdened by the fact that there simply weren't enough hours in the day; simply not enough hands; not enough patience; not enough of me to go around to possibly pull off this wild one-woman show called mothering... the end of believing that I simply wasn't enough.

We walked to school together. Everyone was late. And it was ok.

We walked home together that day too. "You can come over," she said, "but our apartment is a disaster." I didn't care; our's was a disaster too. We made tacos and let the kids destroy the place further in a happy storm of markers and superhero costumes and jumping on the bed. We just sat there and breathed, exchanging war stories and nursing our babies. The babies toddled together, the middle kids bossed around the babies, the big kids mothered them all, and we chaperoned. There were cries and messes, and chaos all around, but for the first time in a long time, if felt ok.

I remember being a new mom, with a slumbering baby girl, reading glossy magazines and blogs full of perfectly happy mothers and their perfectly happy mother friends. They'd talk about their beautiful children, their days at the park, their successful careers, and how they balanced it all. That's what I want for us, I would think. That must be what the old phrase, "It takes a village" looks like!. But I, knowing close to nothing mind you, turned out to be completely wrong. When that illusion was shattered, it took some time for the dust to settle.

A village, as it turned out, and as took me a few years to learn, is not merely a group of friends who are also mothers and whom you meet for play dates and coffee. A village, in my experience at least, is deeper than that. A village means honoring one another even when we feel that we are failing at motherhood. A village means offering understanding and empathy to one another, as all of the trivial yet taxing tasks of the day build up and break us down. A village is more than people- it is a space, created by love, free of judgement, and full of honesty and support. A village means picking up the crying baby, no matter who's baby it is, and slinging him across your hip as if he was your own. It means showing up unexpectedly at a friend's apartment and cooking all the kids breakfast so she can take a shower for the first time in days. It means looking into a friend's tired eyes and reminding her of the queen that she is, even if she feels like her castle is crumbling. Because she damn well is a queen. We all are.

And when we create this village, this space of honesty and support, and these habits of taking care of one another and letting ourselves be taken care of, the most miraculous thing begins to happen. One day the baby's crying (no idea who's baby it is, there are too many to keep track of at this point), and just as you go to sweep him up in your arms, your eldest picks him up and puts him on her hip. And all is well. A couple of days later, one of the toddlers falls off a scooter and scrapes her knee, and you watch as the other children gather around her, lift her up, and encourage her to keep trying. A few weeks later the kids surprise you early in morning with breakfast in bed, a gloriously bland meal of cheerios and grapes. And as they snuggle next to you and your son burrows into that little crook of your arm that he's always loved, he mumbles, "You're the best mama EVER. And you're the most beautiful mama EVER too." It's the best bowl of cheerios you've ever tasted.

I never knew it all, and I don't pretend to now. But if there's one piece of advice I can give new mothers everywhere, that I wish someone had given me (although I am grateful beyond words for the journey that it's been to discover this for myself), it would be: find your tribe. Find the women who will stand with you when the going get's tough, and who aren't afraid to talk about it all.

Find the women who make you feel strong, and heard; help them feel strong, listen to them.

Find the women who aren't afraid of dirt and diapers, who can see the beauty in the chaos, and who understand the transformative power of both laughter and tears.

Find these kindred women and love them. You're children will see the love, and they will mimic it.

And over time, this village will be your biggest support system.

Because over time, my village showed me that the problem was never that I wasn't enough. The problem was that, somewhere along the way, I'd adopted the idea that I had to be.

______________________________________

This post is the first in a writing series I'm collaborating on called #TogetherWeMother with a few other amazing women. Check out their blogs below:

Sometimes Sweet | Bluebird Kisses | Lucky Penny | KikhalyAbove Harrison | Chels and Co. | Petite BietChrissy Powers | Mom Crush Monday | Bonjour Ava | Household Mag

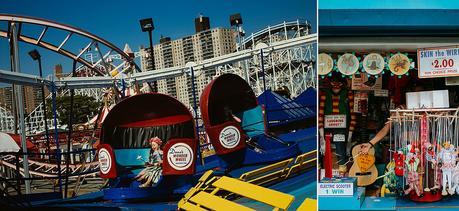

*images are from this summer's Mermaid Parade at Coney Island, to which a friend and I took 7 children. It was amazing.