Another International Women’s Day has come and gone and along with it a rush of activity, offers, events and the usual spate of some men asking “why don’t we have International Men’s Day if we are being equal” (We do, it’s on November 19th and has pretty much the same objective of promoting gender quality). Each year has a theme declared by the United Nation and often other organizations use this theme to base their IWD programs and events as well. For 2017 the theme focused on women in the work place and was ‘Women in the Changing World of Work: Planet 50-50 by 2030’. Now while 2030 seems sometime away, when we look at the status of the global gender gap – one realizes it is an ambitious pledge. Through the Global Gender Gap Report, the World Economic Forum quantifies the magnitude of gender disparities and tracks their progress over time. Their 2016 report stated that at the current rate, (with all things being held equal) the overall global gender gap will be closed in 83 years. This means that baby girls born today, will be lucky to see it close within their lifetime and it will close well after they pass working population demographic.

What does this theme really mean? UN Women Executive Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka in her IWD statement reminded us that we still have significant inequalities in the division of labor across households. You know all that laundry, cleaning, cooking, child-rearing, and household maintenance

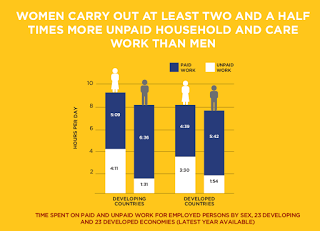

women shoulder? Well it adds up. Women take up nearly double the time doing this than men, and make no mistake, it is work! It is unpaid work that is a larger driver of economies and unfortunately as Mlambo-Ngcuka points out “In many cases this unequal division of labor is at the expense of women’s and girls’ learning, of paid work, sports, or engagement in civic or community leadership”. This has resulted in women lacking choice in what they study or where they work due to this additional responsibility, a significant lack of women in certain industries and occupations, those occupations then lacking support for women with these responsibilities, more women being unable to take those jobs due to the lack of support and the cycle continues.

women shoulder? Well it adds up. Women take up nearly double the time doing this than men, and make no mistake, it is work! It is unpaid work that is a larger driver of economies and unfortunately as Mlambo-Ngcuka points out “In many cases this unequal division of labor is at the expense of women’s and girls’ learning, of paid work, sports, or engagement in civic or community leadership”. This has resulted in women lacking choice in what they study or where they work due to this additional responsibility, a significant lack of women in certain industries and occupations, those occupations then lacking support for women with these responsibilities, more women being unable to take those jobs due to the lack of support and the cycle continues. So where does all this really begin? When do women and girls learn that implicitly they need to shoulder this unequal proportion of household work? Don’t we offer equal education? In Sri Lanka there are more women in university than men, we have female CEO’s, MD’s and the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce is headed by a woman. Isn’t this enough? Apparently not. The number are clear – women still face systematic inequality in the workforce and we need to go back to where it all begins. We need to go back to the classroom, to childhood, to when we are taught 1 plus 1 makes 2 and it seems a lot more than that too.

I was 9 when we were asked to be what we wanted to be when we grew up, and I said I wanted to work for BBC or CNN. “Oh, and doing what sweetie?” they asked, to which with all the unblemished confidence of a 9-year-old I described my vision of covering war zones, volcanoes erupting and marches around the world. Smiles faded and brows furrowed and the answer came, “that’s nice but it might get hard when you become a mommy and your kids need you! Maybe think about being in the studio?”. When my male classmate described his vision of being a pilot, no such advice was given to him. I remember being confused, did that mean he would never be a daddy? Not as often but occasionally the same limitations are placed on our boys, further defining these stereotypes. The lone boy who decided to brave it and take English Literature for A/Levels was subject to double takes and ‘are you sure?’ questions as he sits in a class of girls. Worse is the boy who has no draw to sports and is questioned repeatedly on ‘why not?’, while when the girls request a rugby or football team they are told it is ‘too rough for you’.

This is where it begins – in the earliest days of our children, and is by no means just my story. Nilupuli Andrahennadi is a pilot with Sri Lankan Airlines, one of 14 women among their 300+ pilots. She described how when she was in school she didn't even know piloting was a career option available to women - no one ever spoke about it, nor was there any encouragement of any sort. When she expressed her interest in becoming a pilot more than one person discouraged the idea because it was unconventional and plied her with questions like "how would you raise a family when you will never be at home?". Hiranya Ilango is a filmmaker and described her journey in a field where women are expected to be those who are in front of the camera and never behind it, echoing similar sentiments about her childhood. Dr. Dheena Sadik is a trainer and speaker and shared that despite her struggle to make a mark in male dominated field, she was never given encouragement as young woman and reminded constantly that she was swimming against the tide and destined to fail.

Just recently we were reminded of the uphill climb when Visakha Vidyalaya and Musaeus College

announced their first ‘Big Match’ encounter and foray into a male-dominated tradition – which led to a barrage of ridicule online, including one popular Facebook page parodying the announcement flyer with the caption ‘Battel of the Boobs’ (while the original post has been taken down, the subsequent apology and retraction that was posted has also now gone missing from the page). Jayathma Wickramanayake Dias succinctly put it when she said in a Facebook status, “I’m worried about the little girls who will see those memes and think twice about playing a sport again. I’m worried about the young women who go to sleep tonight unsure if their work will ever be recognized without being made fun of”. These can be passed off as jokes to some, but to others it is a reminder that not all dreams will be deemed valid. That you have a box and breaking out of it means opening yourself to a lifetime of ridicule, insults, and discouragement.

announced their first ‘Big Match’ encounter and foray into a male-dominated tradition – which led to a barrage of ridicule online, including one popular Facebook page parodying the announcement flyer with the caption ‘Battel of the Boobs’ (while the original post has been taken down, the subsequent apology and retraction that was posted has also now gone missing from the page). Jayathma Wickramanayake Dias succinctly put it when she said in a Facebook status, “I’m worried about the little girls who will see those memes and think twice about playing a sport again. I’m worried about the young women who go to sleep tonight unsure if their work will ever be recognized without being made fun of”. These can be passed off as jokes to some, but to others it is a reminder that not all dreams will be deemed valid. That you have a box and breaking out of it means opening yourself to a lifetime of ridicule, insults, and discouragement. Where do we begin? As Mlambo-Ngcuka wrote, “We have to start change at home and in the earliest days of school, so that there are no places in a child’s environment where they learn that girls must be less, have less, and dream smaller than boys”. From the day, the girl child takes her first steps, that is where we must begin. It is then, and only then will ‘Planet 50-50 by 2030’ even seem a remote possibility.

NB: Infographics courtesy UN Women (view the full set here) and Facebook screenshot courtesy Jayathma Wickramanayake Dias