We Heart It

I used to be a book snob: I used bookmarks, never dog-eared, never highlighted nor made notes in the margins. If I let a friend borrow a book and there was so much as a white wrinkle in the spine, I’d get anal. I liked to preserve them in their proper form, which to me meant they should look brand new for as long as I could call them mine. I remember a few years ago, a friend’s mom accidentally spilled tea on my copy of Eragon, then proceeded to lose the book jacket. I thought I’d have a heart attack. The brown stained pages turned stiffly as I flipped through to survey the damage. Lord only knew what condition the book jacket was actually in. Then my cousin told me the copy of P.S. I Love You I bought her for Christmas was eaten by the ocean when she let her friend borrow it on vacation. I couldn’t bear the thought of the water damage.

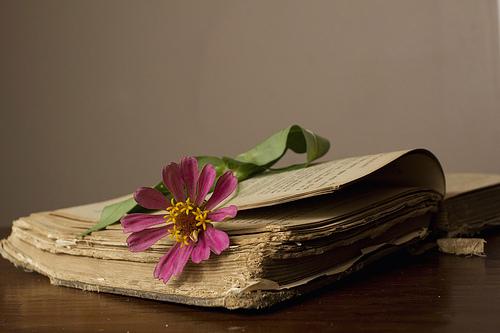

But then something happened. I’m not sure when exactly the change in preference occurred, but somewhere between college and now, I actually started liking the look of worn books. Books that had been read so many times they went limp in your hands; books that flared up at the corners and had slight rips around the edges; books with dedications on the title page; books that had been dog-eared, highlighted, noted in the margins; books that looked like they’d been studied. Books with a history. I began to prefer these books.

The first time I highlighted a passage in a book I’d been reading, my chest slightly tightened. “Oh my Austen! I just defaced a sacred artifact!” I screamed. But then the more I did it, the more right it felt. I scribbled thoughts in one corner, stuck colorful tabs by important sentences, folded corners down on favorite pages. I FELT ALIVE.

“What do you keep highlighting over there?” my co-worker asked me last night. I slid my thick, yellow highlighter down a series of sentences in Madeleine L’Engles, A Circle of Quiet. “Passages.” “What passages?” “Important passages.” “What kind of important passage?” He turned around. “Read me one,” he said in a challenging tone. I flipped through the book and found a paragraph that had stuck out to me earlier on. I cleared my throat.

The moment that humility becomes self-conscious, it becomes hubris. One cannot be humble and aware of oneself at the same time. Therefore, the act of creating—painting a picture, singing a song, writing a story—is a humble act? This was a new thought to me. Humility is throwing oneself away in complete concentration on something or someone else.

“Hm.” Maybe it was just me, but he seemed to suppress a smile. It made me wonder if he wasn’t expecting something so profound. Because Madeleine is nothing if not profound. And that made me smile. I turned back to my book and continued highlighting, and when I was done, I turned down the corner on page 29. Without flinching.