Thanks to William Irvine who has prepared this Independence Day Special article exclusively for Pebble In The Still Waters blog. This interesting article is about three very different, but rare, cases of non-Indians who stayed on after Independence – in Agra, Delhi and Bihar respectively. The article is topical in the run up to the seventieth anniversary on August the 15th. And thus it is featuring on my blog for this special day in our life. Below is a brief about the author.

Independence Day Special Feature

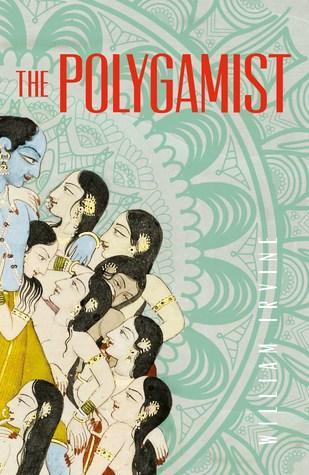

William Irvine has had a lifelong relationship with India, the setting for his novel. Raised in childhood on a relative’s stories of panthers, scorpions and snakes, he jumped at the chance to travel to rural Bihar to work as a volunteer, living at a leprosy hospital in 1978. He read philosophy — his other lifelong passion — at the University of Sussex and has since traveled extensively in South Asia pursuing his interest in Eastern mysticism. After a career in IT spanning thirty years, it is perhaps no surprise that he ended up working for Infosys, one of modern India’s new technology behemoths. The Polygamist is his debut novel

The Polygamist is available via Amazon and other major book retailers.

Find William Irvine on Twitter, Goodreads and Facebook.

So, here goes the Independence Day Special article by William –

Independence Day Special Memoir

People who ‘Stayed on’

India will soon celebrate its seventieth independence day – one of the fifty-nine nations around the world to mark its exit from the British Empire. As August 15th, 1947 approached, India’s expats would have held many conversations about ‘staying on’. Whilst many discussed the prospect, few did. I have been fortunate to have known a handful of individuals who did stay on. These are their stories.

Independence Day Special – People Who Stayed On

Source: http://www.officeholidays.com/

Source: http://www.officeholidays.com/

I met Mrs. Mukherjee, a short round septuagenarian, in a New Delhi suburb in 1978 whilst staying as a guest at the home of her next door neighbor, a Scottish nurse. My host had once been a volunteer worker in Chennai and lived with her adopted daughter, a pretty five-year-old Tamil whom she had nursed back from marasmus. The girl’s natural mother, a street prostitute, had been trying to starve the baby to death. Mrs. Mukherjee always wore a white sari – presumably because doing so emphasised the slight tan on her skin, helping her to blend in a little better with the locals. My enduring memory of her was of her racism. Mrs Mukherjee was German and a committed Nazi.

With the thickest of accents, she used to berate my host for having adopted a Dravidian: ‘Ach, this is so bedt! Why could you not hef adopted ein Ayrian kind?’ Amazingly, my host managed to take these comments in her stride – gently and good-humouredly scolding Mrs. Mukherjee for her bigotry – I know she found them deeply offensive. When Mr. Mukherjee – who no doubt was as fine an example of Aryan manhood as ever walked this Earth – died ten years after Independence he must have left his widow with a dilemma. Should she return to a de-Nazified Germany, an unfamiliar country transformed since she was last there? Or, should she isolate herself from it – remaining in the time warp that living in her husband’s country provided?

Independence Day Special 1947-2017

Another person who stayed that I came to know was ‘Sister George’, a nurse and a Baptist missionary. Originally from Enfield – the town a little north of London where the motorcycles of the same name were once made – she lived in an enormous mission house a couple of miles outside Jamtara, a sleepy Bihar town on the Delhi-Kolkata line. Somewhat isolated, the husband who had once evangelized at her side was buried under a stone cross in the house’s extensive grounds. Also in her seventies, retired, she passed her days reading the Bible, praying and managing her garden – an oasis surrounded by her farmer-neighbours’ soil-eroded fields. She took great pleasure in the golden orioles and other exotic birds that were attracted to the garden’s many mature trees.

Chowkidars kept the place secure whilst her remote American backers ensured she was comfortable – her table was the only place in India that I was served frozen peas in the seventies. They were imported, she said, ‘in a barrel from the UK’. I asked if she had ever considered returning. ‘What on Earth for?’ she responded, ‘I’ve built my whole life here.’ Bihar gave her purpose. Deprived of it in the UK, she would have been like a fish out of water.

Independence Day Special on Expats

How these two women came to be in India is similar to the pattern of expat immigration throughout the colonial period. Foreigners came out for a purpose. In the days of Company rule young Englishmen arrived in Bengal hoping to return rich – and some of the ones who didn’t end up in Kolkata’s churchyard cemeteries did. After 1857, during the Raj and once Westminster had reigned in the excesses of the East India Company, British emigrants to India (who curiously were more often Scots than English) went out to pursue careers in the Indian Civil Service, the judiciary, the Indian Army or the Police Service – always planning on a retirement back in the UK. It was an altogether different model to that in other parts of the Empire.

British emigrants to Canada, Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, pre-revolutionary America, New Zealand or the West Indies went out in order to settle in those countries permanently. It is therefore not surprising that after 1947 only the odd widow or person too elderly to start again in their mother country remained.

Independence Day Special remembring emigrants

The John family is an exception as rare as a white tiger. In 1966 a sister 12 years my senior introduced Victor John – the young man whom she went on to marry – to my family. Having grown up in India, Victor was full of stories that, as a young boy, I found fascinating. He was a demon mechanic, spoke fluent Hindi, and made amazing kites using only paper, twine and a pair of sticks. Many of his Indian tales – probably passed down through the several generations of his family – contained a practical lesson. To hunt a black panther, for example, one must tether a goat in open ground on a moonlit night and then watch from a tree downwind of the bait. Being almost invisible in the dark, one must listen for the creature’s arrival, and then aim a rifle between its luminous green eyes.

How did Victor come to be raised in India after Independence? His first name requires no explanation – he was born in 1945. However, the surname ‘John’ is unusual, being a name legally changed and anglicized by a Greek ancestor, Ioannides. A ‘soldier of fortune‘, Mr. Ioannides/John turned up in India in 1800. Being the period of its most aggressive expansion, the East India Company would readily have hired him. In 1805 he fought in the Second Anglo-Maratha War at the siege of Maharaja Holkar’s virtually impregnable Bharatpur fortress. The defenders successfully beat off all four British assaults, inflicting high casualties. Bharatpur did not fall until the Third Anglo-Maratha War, in 1826. The city of Agra came under Company control as an outcome of the Second War, Mr. John probably settling there opportunistically at its end.

Independence Day Special – What after Independence

His descendants ran textile mills, producing cloth for the domestic market, avoiding the need to ship Indian cotton back to Lancashire as was then the norm. Sidney and Beatrice Webb – the Fabian socialists who founded the London School of Economics and the ‘New Statesman’ magazine – briefly mention the John family’s mills in their ‘Indian Diary’ of 1911-1912, noting the grim working conditions. This fits with one of Victor’s stories about an unfortunate employee who lost an arm in the machinery one week, only to lose the other a fortnight later while demonstrating how the original accident had happened.

By 1855 the Johns were wealthy enough to build their own Anglican church (‘St John’s’ naturally) on Agra’s Hospital Road – a substantial building that would look more at home in Surrey. The large compound where they lived, with its gate house wide enough for a Rolls Royce to pass through, is there to this day. After Independence, the family wealth went the same way as that of the Princely classes’ – being subject to the same draconian taxes that socialist Pandit Nehru brought in in order to deliver the coup de grace to the old order. Staying on might not have been one of the Johns’ better decisions.

Nevertheless, Victor’s father, uncle and an elderly aunt were still living at the compound when he and my sister visited in the nineties. My sister described the father as a man ‘with attitudes belonging to a different era’ who still complained that ‘the club wasn’t the same anymore since it had started admitting Indians.’

Independence Day Special – Story of Victor

Victor described, but would have been too young to have witnessed personally, the horrors of Partition – of corpses lying in the gutters with their throats cut – but his parents would not. There was also an incident in which, as a teenager, he himself was nearly murdered. Two thugs pinned him against a wall while a third produced a blade. Luckily a friend saw and intervened. Against this background, his parents decided there was no future for their four sons in India. They exported them (or ‘repatriated’ them, depending on how you see things) to the UK. My sister describes how lost the brothers seemed, finding London no less alien than any other immigrants would. Victor’s father died in Agra in 2001, drawing to a close a family dynasty of two hundred years.

I visited India myself for the first time in February 1978. As I journeyed from Delhi to Bihar on the (extremely slow) ‘Toofan’ Express I was fascinated by the sights and smells of a country so different to my own. However, I kept hoping the train might pass a forested area – the sort of place where so many of Victor’s tales of snakes and tigers had been set – but it never did. On that journey it gradually dawned on me that the forests no longer existed – nor did the India he had described (if it ever had).

I arrived at the leprosy hospital where I was to be based wearing ‘desert boots’ – suede ankle boots fashionable at the time. The locals correctly advised me to wear a pair of cooler, more practical, chappals instead (called ‘flip flops’ in England because of the sound they make). I stored the boots in a cupboard and forgot about them for the next several months. When it was time to leave I retrieved them, intending to wear them on my subsequent travels. Before putting them on I turned them upside down and whacked them together several times. A rather dazed garden spider fell out. Victor had advised me to always do this – scorpions often crawl inside empty boots…

William Irvine is author of The Polygamist.